Capital gains taxes represent a fundamental aspect of personal finance, investment strategy, and government revenue. For individuals and businesses who engage in the sale of assets—ranging from stocks and bonds to real estate and collectibles—understanding how capital gains taxes function is essential for effective financial planning. This article explores the nuances of capital gains taxes, examining their definitions, calculation methods, tax rates, exemptions, practical examples, and future trends affecting taxpayers and the economy.

The Role and Definition of Capital Gains Taxes

Capital gains taxes are levied on the profit earned from the sale of a capital asset. A capital asset includes any property held for investment or personal use, such as stocks, mutual funds, real estate, jewelry, or art. The key element that triggers such taxation is the gain—the difference between the selling price and the original purchase price (or basis). For instance, if an investor buys shares for $10,000 and later sells them for $15,000, the capital gain is $5,000, which may be subject to taxation.

Governments impose capital gains taxes to generate revenue and regulate economic activity. Unlike ordinary income, capital gains often receive favorable tax treatment as an incentive for investment. According to the Congressional Budget Office, capital gains taxes accounted for roughly 10% of federal individual income tax revenue in recent fiscal years (CBO, 2023). This underlines their importance both to taxpayers and public finances.

Differentiating Short-Term and Long-Term Capital Gains

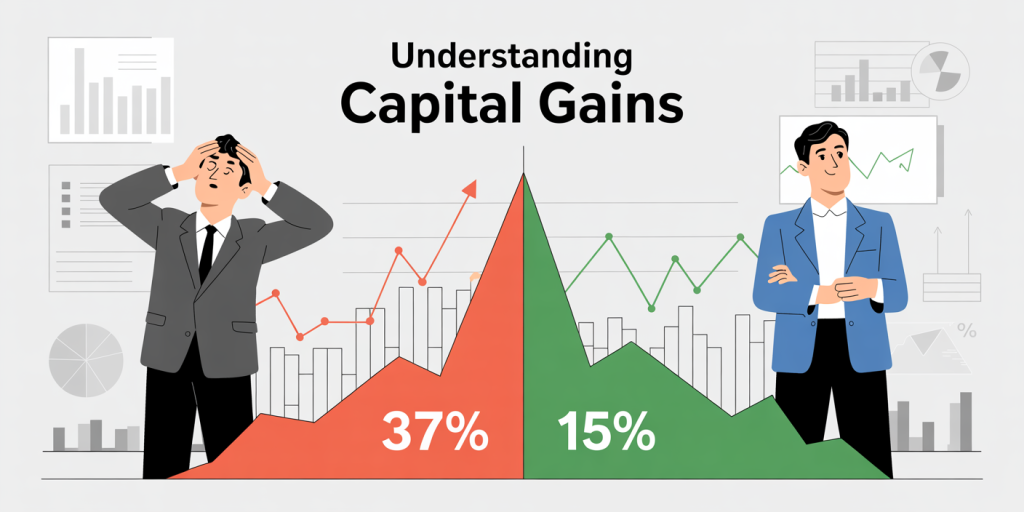

One of the critical distinctions in capital gains taxation is the holding period, which determines whether gains are classified as short-term or long-term. Short-term gains apply to assets sold within one year or less from the date of purchase; these are typically taxed at ordinary income tax rates. Conversely, long-term capital gains arise from assets held longer than one year and benefit from reduced tax rates.

For example, consider an individual who buys stock for $5,000 and sells it six months later for $7,000, realizing a $2,000 gain. This $2,000 is short-term and taxed at the taxpayer’s marginal ordinary income tax rate, which might be as high as 37% depending on income level. If the same stock was held for 18 months before selling, the $2,000 gain would be taxed at long-term rates, which for 2024 range from 0% to 20%.

| Holding Period | Tax Treatment | Tax Rates (2024) |

|---|---|---|

| Short-term (≤ 1 year) | Taxed as ordinary income | 10% to 37% |

| Long-term (> 1 year) | Preferential capital gains rates | 0%, 15%, or 20% based on income brackets |

This distinction plays a vital role in investment strategies. Many investors plan asset sales with the aim of qualifying for long-term capital gains rates, which can result in significant tax savings.

Calculating Capital Gains and Adjusted Basis

Calculating capital gains accurately requires understanding the concept of “adjusted basis,” which is the original purchase price of an asset adjusted for various factors. These adjustments can include commissions, improvements to property, depreciation, and certain costs associated with the purchase and sale. For example, when selling a home, capital improvements like installing a new roof or renovating a kitchen can increase the basis, reducing the taxable gain.

Consider a real estate investor who buys a property for $200,000, spends $30,000 on renovations, and sells the property years later for $300,000. The adjusted basis would be $230,000 ($200,000 purchase price + $30,000 improvements). Therefore, the capital gain would be $70,000 ($300,000 – $230,000), not $100,000. Ignoring the basis adjustment would result in a higher, potentially inaccurate taxable gain.

Another important point is that selling costs such as broker fees or legal fees are subtracted from the sales price when calculating capital gains. For instance, if the aforementioned investor paid $10,000 in selling costs, the net selling price would be $290,000, lowering the gain to $60,000 ($290,000 – $230,000).

Exemptions, Exclusions, and Special Cases

In the U.S., several exemptions and exclusions could reduce or eliminate capital gains taxes under specific circumstances. One of the most commonly used provisions is the Section 121 exclusion on the sale of a primary residence. Taxpayers may exclude up to $250,000 ($500,000 for married couples filing jointly) of capital gains on the sale of their primary home if they meet certain residency and ownership conditions.

For instance, a couple who buys their house for $400,000 and sells it for $700,000 after living there for more than two years can exclude up to $500,000 of the $300,000 gain, resulting in no federal capital gains tax liability. This exclusion encourages homeownership and provides tax relief to ordinary homeowners.

Other special cases include the capital gains treatment of inherited property, which benefits from a “step-up” in basis. For example, if an heir inherits real estate valued at $500,000 but purchased decades ago for $100,000, the basis is “stepped up” to the $500,000 market value at the time of inheritance. Thus, if the heir sells the property soon after, there is minimal or no taxable capital gain.

Practical Examples and Real-World Scenarios

To illustrate capital gains taxes further, consider two typical investors:

Example 1: Stock Investor with Long-Term Gain Maria buys 100 shares of a company at $50 per share ($5,000 total). After holding for 2 years, the stock price rises to $80 per share. Maria sells all shares for $8,000, generating a long-term capital gain of $3,000. Suppose Maria’s income places her in the 15% long-term capital gains bracket, so she owes $450 in taxes ($3,000 x 15%).

Example 2: Flipping Real Estate John buys a property for $250,000, renovates it for $40,000, and sells it within 8 months for $340,000. Since the property was held under one year, any gain is classified as short-term. John’s adjusted basis is $290,000 ($250,000 + $40,000), and the gain is $50,000 ($340,000 – $290,000). Assuming he is in the 35% tax bracket, John owes $17,500 in taxes ($50,000 x 35%).

These examples underscore how timing, holding period, and income level impact capital gains taxes and reinforce the need for strategic asset management.

Capital Gains Tax Rates Around the World

Capital gains tax rates vary globally, reflecting differing tax philosophies and economic policies. A comparative overview reveals wide disparities:

| Country | Capital Gains Tax Rate | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| United States | 0% – 20% (long-term based on income) | Preferential rates for long-term, exemptions apply |

| United Kingdom | 10% – 28% | Higher rates for residential property, allowances |

| Canada | Taxed as ordinary income at 50% inclusion rate | 50% of gains included in taxable income |

| Australia | 0% – 45% (50% discount on assets held >1 year) | Discount on gains for long-term holdings |

| Germany | 25% flat (plus solidarity surcharge) | Exemptions for assets held over one year if private |

| Japan | Approximately 15% combined national and local taxes | Distinct rates for different asset types |

Understanding these international variations is critical for investors with cross-border portfolios or those considering relocation.

Future Perspectives on Capital Gains Taxation

Capital gains taxation continues to evolve alongside economic shifts and political debates. Recent proposals in the United States have considered increasing the top capital gains tax rates to align more closely with ordinary income rates, aiming to address wealth inequality and generate additional revenue (Treasury Department, 2024). For example, some lawmakers advocate taxing capital gains over $1 million at ordinary income rates, potentially raising the highest rate from 20% to 39.6%.

Beyond rate adjustments, technological advancements in financial data analysis and blockchain may improve tax compliance and transparency, reducing tax evasion related to capital assets. Legislative reforms may also expand reporting requirements for cryptocurrency transactions, where defining taxable events poses new challenges.

Environmental and social governance (ESG) investing could influence capital gains strategies, with parameters for tax incentives tied to sustainable assets or green bonds. Additionally, demographic trends such as aging populations and rising retiree wealth might provoke changes in estate tax and inherited capital gains rules.

Taxpayers and financial planners must stay informed of these developments to optimize tax efficiency and comply with future regulations.

In summary, capital gains taxes are a pivotal component of the tax framework affecting a broad range of assets and investment strategies. From distinguishing short-term versus long-term holdings to leveraging exemptions and understanding international comparisons, mastery of capital gains tax principles enables taxpayers to make informed decisions that can save substantial sums and support long-term wealth accumulation. As the tax landscape evolves, ongoing education and strategic planning will remain indispensable tools for navigating capital gains obligations effectively.

Deixe um comentário